PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwayNew James Webb Space Telescope observations of the third world in the seven-planet TRAPPIST-1 system rule out a variety of atmospheres.

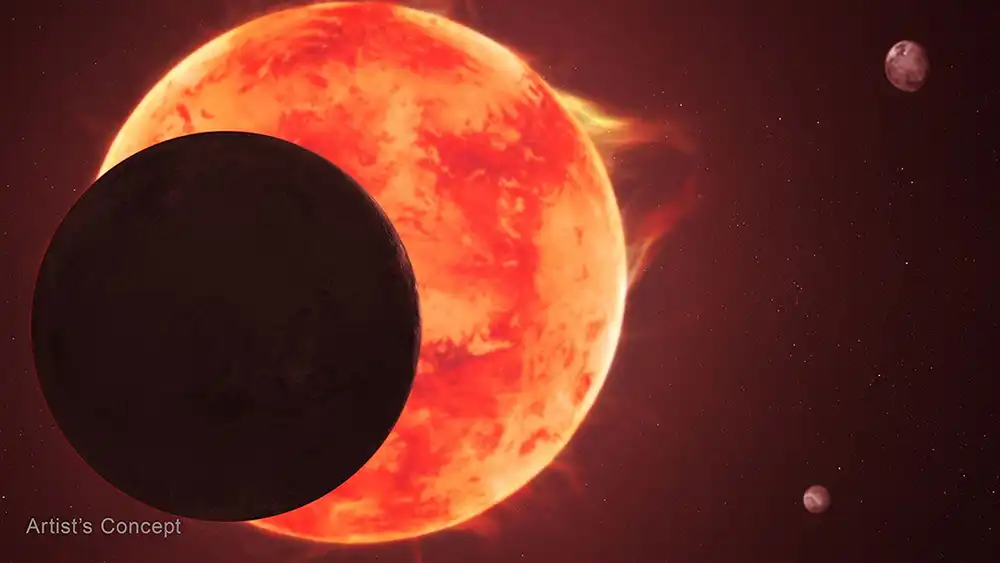

This artist’s concept depicts planet TRAPPIST-1 d passing in front of its turbulent star, with other members of the closely packed system shown in the background. The star is a tenth the Sun's diameter, and the planet is not quite as large as Earth.

This artist’s concept depicts planet TRAPPIST-1 d passing in front of its turbulent star, with other members of the closely packed system shown in the background. The star is a tenth the Sun's diameter, and the planet is not quite as large as Earth.NASA / ESA / CSA / Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

TRAPPIST-1 is a planetary system quite different from our own — and one of the best places we know of to look for planets like ours. Yet near-infrared observations from the James Webb Space Telescope now reveal that this world, like the innermost two, is likely an airless rock.

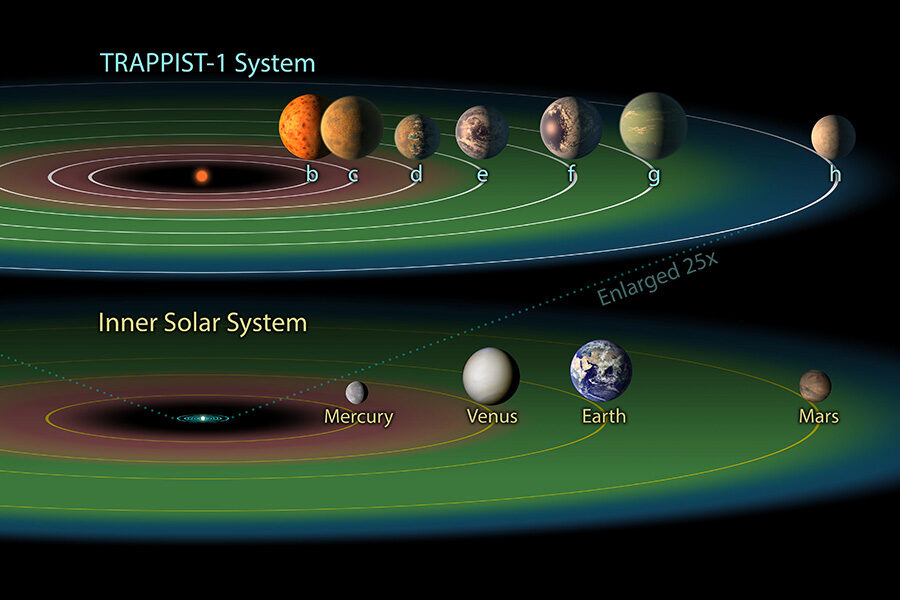

The red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1 has a tenth the span of our Sun and hosts seven rocky planets. Their orbits are short — a year on these planets amounts to at most two weeks on Earth. Yet because the star is so puny, three of these worlds (TRAPPIST-1e, f, and g) are in the habitable zone, where liquid water has the potential to be stable on the surface in the presence of an atmosphere.

Whether there’s atmosphere on any of these worlds is an open question, but not for long. At only 40 light-years away, the planets are easy pickings for Webb, which is one by one taking the measure of these planets as they orbit their star. Those observations have already shown that TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1c are bare worlds, but that wasn’t a surprising find — climate models had already predicted that the puny star’s flares and radiation would strip the atmosphere of these close-in worlds.

There was more hope for TRAPPIST-1d, even though it's just inside the habitable zone. One climate model predicted a 70% chance that it would host an atmosphere. But now the results are in: Webb took near-infrared spectra of the planet as it passed in front of its star twice last November. This transmission spectroscopy allows astronomers to subtract out the star’s light (not an easy task) to reveal the sliver of starlight that’s passing through the planet’s atmosphere.

The results, published in the Astrophysical Journal in a study led by Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb (University of Montreal) are discouraging. The spectrum is flat: There are zero chemical fingerprints of water, methane, carbon dioxide, or any other molecules that the team searched for. There isn’t even a gentle slope to the spectrum that would indicate a haze like we see on Titan.

The TRAPPIST-1 system contains a total of seven planets, all around Earth's size. Three of them — TRAPPIST-1e, f and g — orbit in the star's so-called "habitable zone," a band (shown here in green) in which liquid water might exist on a rocky surface. In making these calculations, astronomers typically assume the planet has some kind of atmosphere.

The TRAPPIST-1 system contains a total of seven planets, all around Earth's size. Three of them — TRAPPIST-1e, f and g — orbit in the star's so-called "habitable zone," a band (shown here in green) in which liquid water might exist on a rocky surface. In making these calculations, astronomers typically assume the planet has some kind of atmosphere.NASA / JPL-Caltech

Two options remain. TRAPPIST-1d is most likely an airless world, like the closer-in b and c. But it’s still possible that the planet hosts a very thin, carbon dioxide-dominated atmosphere, like that on Mars, or even that it hosts thick clouds, like Venus, that prevent us from seeing into the atmosphere.

Assuming the planet really is airless, the observations suggest that TRAPPIST-1b, c, and d formed fairly dry, because if they had significant amounts of water, we’d still see some of it. (“Dry” in the context of planet formation means that they formed with less than four Earth oceans’ worth of water.)

Even an airless TRAPPIST-1d doesn’t mean we should give up on this system altogether. After all, Mercury, Venus, and Mars would likewise discourage alien observers of our system. TRAPPIST-1e, f, and g are all more likely to have an atmosphere because of their greater distance from their star — as long as the puny star’s outsize flares haven’t stripped those atmospheres, too. Webb-based studies of the outer TRAPPIST planets are forthcoming.

3 days ago

7

3 days ago

7

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·