PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwaySeabirds are fascinating, but they can also be elusive and difficult to see, which goes someway to explain why the biggest gaps in my life list are the seafaring species. OK, I’ve been lucky enough to have seen six species of albatross, but that does mean there’s another 16 I haven’t seen. My score of 20 petrels sounds pretty reasonable, but that still leaves another 80 I’ve never set eyes on.

I clearly haven’t spent enough of my time seawatching, travelling on ships to remote islands, or on dedicated pelagic outings. Until last month I’d only done two pelagics in my life. The first was off Cape Town in the early 80s and was memorable for seeing albatrosses and Sabine’s Gulls. The second was from Wollongong in Australia in the late 90s. A highlight on this trip was feeding chum to White-chinned Petrels by hand, and the Wandering Albatross that ate so much chum it was doubtful whether it could take off again. It was also an uncomfortable experience in choppy waters: my companions all swore that they would never do another pelagic.

Look carefully and you will see the Marilimitado rib setting off from Sagres harbour (photo by Jan Tomlinson)

Fortunately I don’t get seasick, which was a reassuring thought as I set off last month on my latest pelagic. I was riding in a rib (the term for a large sea-going inflatable, equipped with powerful outboard), in company with a dozen other adventurers. Our departure point was Sagres, the most south-westerly point on the European continent. The weather was kind, with brilliant sunshine and little wind, but the sea was lively, which made riding the rib – you sit astride rather than on a seat – exhilarating.

You sit safely astride the seats in the rib

The pelagic was organised Marilimitado, (https://marilimitado.com/tours/seabird-watching) a company run by marine biologists; it offers dedicated seabird watching excursions, as well as ocean safaris and dolphin watching. It was reassuring to know that I was in both safe and experienced hands, and our captain certainly knew how to handle the boat, which he did with great skill. But could he find the birds for us? The list of possibilities was considerable, and ranged from four species of skuas to a variety of shearwaters and petrels.

An adult Lesser Black-backed Gull

First-winter Yellow-legged Gulls (above and below)

We all know that birding can be a matter of luck, and seabirding particularly so. We weren’t, alas, lucky on this trip, as the variety of species we came across was low, but what we did see was for me a real treat. It was also an introduction to the challenge of trying to identify and photograph birds from a small boat, rolling in the waves. Everything about the photography was difficult, from managing to find the bird in the viewfinder to shooting with the right exposure. I took a considerable number of shots of an empty sea, with not a bird to be seen. Even using binoculars was tricky.

Improbably long-winged, Gannets displayed a variety of plumages

For the first half hour there were few excitements. The most numerous birds we saw were Lesser Black-backed and Yellow-legged Gulls, neither of which require a pelagic to view them. There were also a number of Gannets, displaying a rich variety of plumages from first-year birds to full adults – they take five years to gain full plumage. I failed dismally in my efforts to expose for a brilliant white gannet swimming on a deep blue sea.

First view of a European Storm Petrel

European Storm Petrel. The broad white band on the underwing is diagnostic

Then, suddenly, the first petrel – a European Storm Petrel – appeared fluttering over the waves, looking much like a House Martin with its dark back and contrasting white rump. Size-wise it’s only marginally bigger than a House Martin, so the comparison is a fair one. Seeing storm petrels from shore is difficult, so these first views were a delight. Minutes later we encountered our first Cory’s Shearwaters. The skipper slowed the boat, and I even managed to get a few sharp pictures. Though I’ve seen Cory’s many times, as they are relatively easy to see from the shore, this was the first time that I’d ever tried to photograph one.

Cory’s Shearwater (above and below).

Our skipper was looking for rafts of seabirds, but there were no fishing boats in the vicinity, so nothing really to attract the birds. We did eventually come across a group of about 100 large gulls, and swimming with them was a single shearwater: it proved to be a Great Shearwater, a bird that was a lifer for me (see header photograph). Minutes later I photographed another as it flew past the boat, a highly satisfying moment, as it was my first lifer in Europe since 2019.

Great Shearwater (above and below). A long-awaited lifer

Encouraged by the presence of the gulls, the skipper decided to throttle back the engine and chuck out the chum – the smelly food that draws in the petrels. He promised that within a few minutes there would be a number of storm petrels around the boat. Sure enough, there were soon a dozen or so of these birds, fluttering around, offering tempting but usually impossible targets for my camera. Watching these delicate little birds, seemingly walking on the water, was a memorable experience. Using binoculars was difficult, so I concentrated on trying to take photographs instead.

Wilson’s Storm Petrel. A species that breeds in the southern hemisphere but which can be seen reliably off the coast of Portugal. Note the dark underwing of the bird above

This bird is revealing the diagnostic yellow webs of a Wilson’s Storm Petrel

The diagonal wing bar is a feature of Wilson’s Storm Petrel

Wilson’s Storm Petrels have proportionately longer legs than European Storm Petrels. As this photograph shows, their legs appear both long and delicate

Though I was well aware of the possibility of seeing Wilson’s Storm Petrels as well as the slightly smaller European Storm Petrels, I didn’t consciously notice any. The differences between the two are subtle, though I’m sure that separating them is easy with practice, that was something I didn’t have. It was only when I was back on dry land, enjoying a lunch of grilled sardines in Sagres, that I had the chance to scroll through the photographs on the back of my camera. Almost at once I spotted that some of the petrels I’d photographed had yellow webs to their feet, a reliable identification feature for Wilson’s. Curiously, the majority of my photographs proved to be shots of Wilson’s rather than European Storm Petrels, suggesting that the former were the most numerous.

Shags are common on inshore waters around Sagres

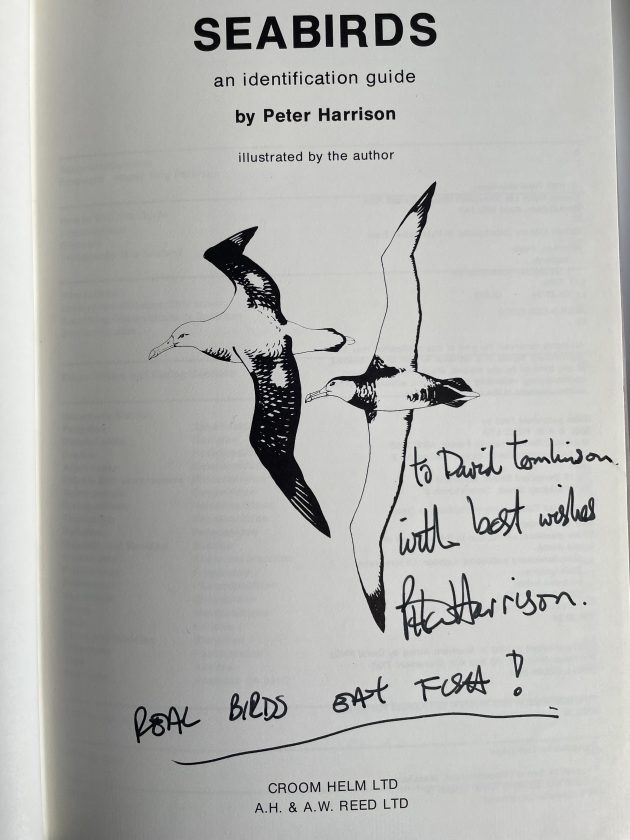

After our chumming session it was time to head back for land – the outing was for two and half hours, and time was pressing. Our skipper hoped to add some extra species on our return, but the only ones we scored were Audouin’s Gulls and Shags. It had, however, been a terrific outing, and the highlight of my birding year. It reminded me of what seabird guru Peter Harrison had inscribed in my copy of his book Seabirds; an identification guide. “Real birds eat fish”.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·